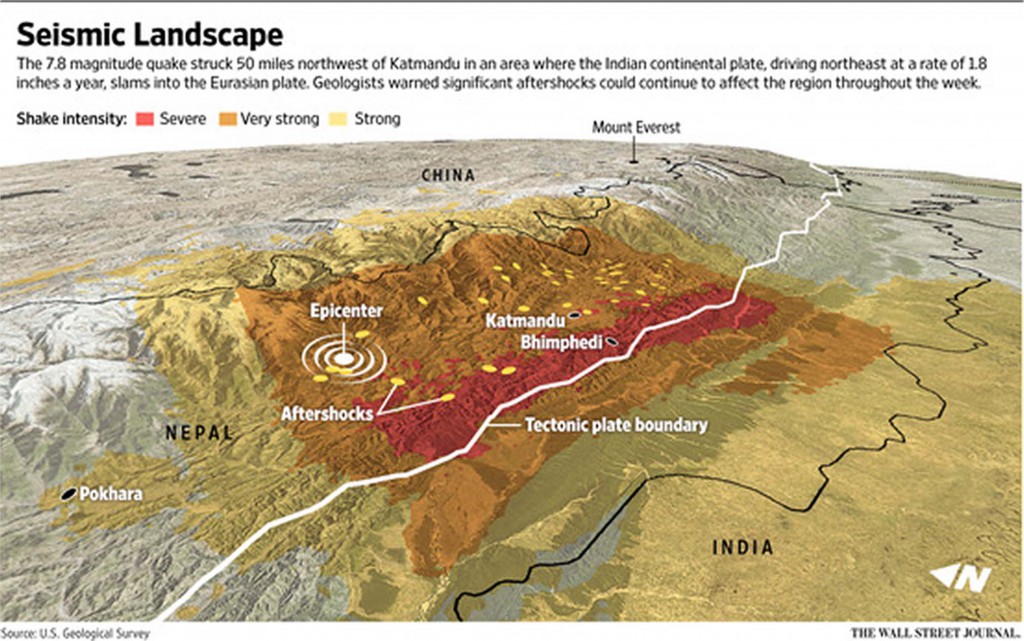

In the sunny day on April 12, 2015, at 11:56 local time, a strong earthquake jolted the terrains of Kathmandu Valley. Series of aftershocks in the following months left around 9000 people dead and about half a million of structures collapsed in the zones hit by the earthquake. The magnitude measured is 7.6 and the jolt was experienced for about two minutes. At 12:20, it was again hit by a shock of 6.6 and next day by that of 6.9. Another powerful shock of 6.8 on May 12 further damaged the buildings made vulnerable by the first motion and the series of aftershocks. The epicenter of the first jolt was 76 km northwest of Kathmandu in the district of Gorkha in the village of Barapak, and of the aftershocks in the neighboring regions (Fig 1).[1] In Barapak itself among its more than 1100 households, only two units in masonry and about 20 RCC units survived taking a toll of 72 lives (Fig 2a,2b). [2] The human loss would have been much more if it was not simply for the reason that people were out of their home at this day time following usual routine schedules. The school children also were not in the school as it was the weekend day.

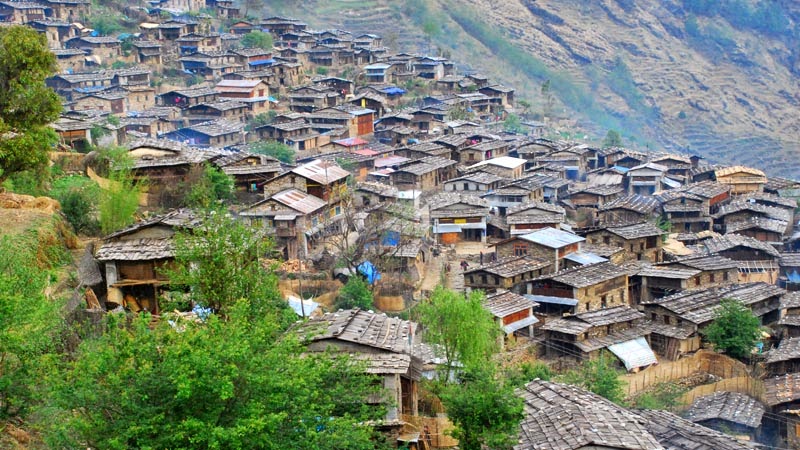

Fig 1

Fig 2a

Fig 2b

Symbolic representations of the damage of this earthquake abound in papers and in websites. Among them is the collapse of Dharahara, a structure of 62 m height first built in 1832 and rebuilt after the 1934 earthquake (Fig 3a,3b). The tower built in fired brick with special mortar that uses lentil, molasses and lime collapsed breaking at its second ring with a slash of about 45 degree. The tower served as a city symbol as it could be seen from many locations of the city. Human casualty is thought to be considerable since there were people at the viewing balcony of this tower, and movement of people in the square around it is always substantial. Another image was a section of a highway connecting Kathmandu and Bhaktapur that sunk by about 1 m from the original road level (Fig 4). The author could observe a crevice of more than two meter deep in the fissure thus created. After around two months, the depressed section of the road was filled up restoring the normal flow of this arterial traffic. But Dharahara is now a point of debate on its cultural and historical significance, and the fate remains uncertain.

Fig 3a

Fig 3b

Fig 4

To the international community, the scene of damage of the World Heritage Sites—the palace sites of the three cities, and Swayambhunath was enough. In Bhaktapur Palace Square, five monuments are destroyed of which a Sikhara style temple dedicated to Vatsala Devi built in stone totally collapsed from the plinth level (Fig 5). A number of other structures suffered serious damage whose walls are now given temporary support from sideways by means of timber posts (Fig 6). The five story temple, the symbol of Bhaktapur, standing 30 m high from the ground with a high plinth of 8 m in five receding levels, however, remained intact except the damage at the corner of its topmost level (Fig 7). The temple also had remained intact in the previous earthquake of 1934 whose shock, according to the people who experienced it, was much greater than the present one.

Fig 5a

Fig 5b

Fig 6

Fig 7

The degree of damage in Patan Palace Square and in Hanuman Dhoka Palace of Kathmandu is even severe compared to the scene of Bhaktapur. In Hanuman Dhoka Palace Square, either there is a complete collapse of the structures, or the structures suffered serious damage which requires reconstruction (Fig 8). The complete collapse of Kasthamandap, an ancient wooden structure confirmed from 12th century records, is a testament to judge the level of consciousness of the concerned institutions such as the Department of Archaeology with respect to the vulnerability of historic structures, and on the precautionary measures that should have been taken before any of such disaster takes place (Fig 9a, 9b).

Fig 8

Fig 9a

Fig 9b

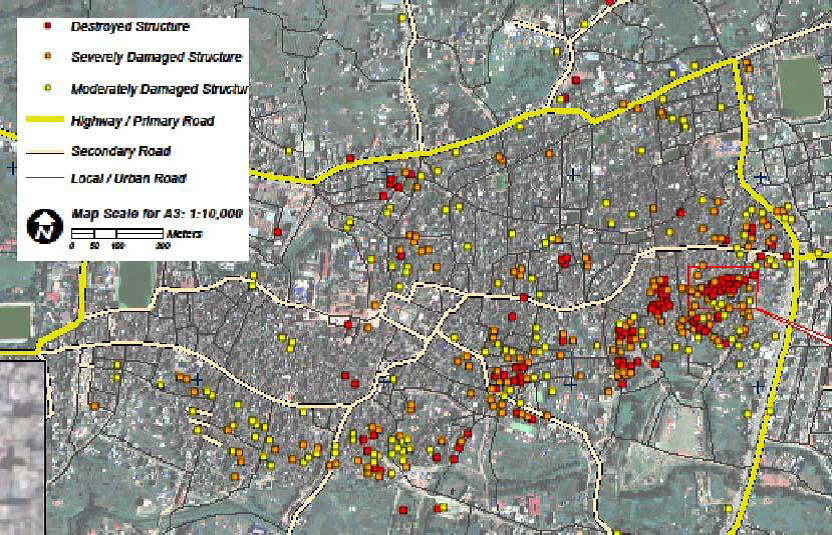

The pattern of damage in the Kathmandu Valley suggests that the tremor hit particular locations more strongly than others. Settlements at the south east direction suffered more than elsewhere. And settlements with soil strata of rock and gravels didn’t suffer much. The buildings that suffered serious damage belonged to relatively older age which was built in brick with mud mortar. The study of various damage situations suggest that the damage occurred more in cases where there was lack of horizontal tie up with the vertical member such as wall masonry.

Structures that are relatively new, of about 30-40 years, are built in RCC of which a greater majority is built in the past 15 years. This is particularly the case in residential units. These buildings by and large remained intact at least in their structure frame. In certain cases, serious damage occurred such as pancake collapse of the whole building, and falling of infill brick walls of the high rise apartment buildings (Fig 10, Fig 11). These represent situations of design and construction faults that ignored either the nature of soil strata or consideration of the common situation of building damage to be found in the seismic movements.

Fig 10

Fig 11

The April 25 and the May 12 tremor hit 31 districts of Nepal causing damage of different degrees of which 14 are crisis-hit. Around 9000 people lost their life and 22000 were injured. The governments of Nepal figures indicate that 602,257 houses were fully damaged, and 285,099 houses were partially damaged.[3] The Ministry of Home Affairs has classified the affected regions into three categories—severe, medium and relatively less damage. 14 districts that include Kathmandu valley and its neighboring regions belong to the category of first severity. The total damage due to the quake to the entire country that includes private dwellings, educational and health facilities, government institutions and infrastructure has been estimated to reach 7 billion US dollars.[4] The Post Disaster Needs Assessment (PDNA) done by National Planning Commission at the end of May 2015 gives breakdown in each cluster of services.

With respect to the temporary shelter to be provided, there are no acts and regulations that stipulate government’s responsibility to the citizens. Ministry of Home Affairs, which holds the responsibility with its Disaster Management Control Unit, didn’t come to the stage to supply the emergency shelter units. The municipalities and district offices did coordinate the donation activities by nongovernmental initiatives but didn’t have their own guiding relief activities with respect to the sheltering places.

People took shelter particularly in places such as in the urban squares, school grounds, and residential courtyards (Fig 12a, 12b). In the historic cities of Kathmandu Valley, Buddhist vihara courtyards proved to be of particular importance as emergency shelters. Probably all viharas of the Valley served this purpose with their limited open and sheltering space. Worst as sheltering place were the highway sides where one could find instances of people taking shelter in the green belt at the middle of the highway and using bus stop sheds. The largest shelter ground was the Tudikhel located at the east of the old city area of Kathmandu (Fig 12c).

Fig 12a

Fig 12b

Fig 12c

What the government did with respect to the emergency shelter is the distribution of a limited quantity of tarpaulin sheets of 3.6 x 5.4 m size per family unit. Our observation visit shows that all the tents were supplied by international donors and religious institutions. And a great many of them were covered by plastic sheets that was either in the stock of the people or, if not, bought by the people themselves (Fig 13).

Fig 13

As the days passed on, the rainy season was nearing and the emergency shelters with tarpaulin or tents evidently were not going to protect the inmates from the weather. A shelter that could last for a period before one could move to the permanent home was of immediate necessity. But the government again was unprepared. There doesn’t exist standards to guide the construction of temporary shelters such as that on floor space and other quality matters. The government simply resorted to a measure declaring a support of RS 15000 asking the people to buy CGI sheets to protect them from the weather. The amount was intended for the roofing of two rooms.

The philanthropic organizations were quick from the beginning to provide CGI sheets for the shelter. There were already temporary unit models of CGI sheet material that covered both wall and the roof (Fig 14, 15). People consequently followed the CGI box model for their temporary dwelling unit. However, a unit of 3 x 4 m when covered with cgi sheet both in wall and roofing did cost around Rs 40,000. Yet by now, a great many varieties of such temporary sheds are to be found. Such sheds use recycled material from bricks, CGI sheets to doors and windows ( Fig 16a, 16b). These materials supplement to the Rs 15000 support by the state to get the cgi sheet and minimize the cost in building the shed.

Fig 14

Fig 15

Fig 16a

Fig 16b

At present, in Bhaktapur, which suffered more damage in the city scale compared to Patan and Kathmandu, municipal records show that 6411 dwellings out of about 18,000 units in the historic town area suffered total damage (Fig 17a, 17b). More than half of the population has to shift either to temporary shelter or find rooms in rent (Fig 18). A considerable number of households live in their relatives’ place. It has been phenomenal that the houses whose upper story collapsed or suffered serious damage are cleared or dismantled leaving only one level over the ground floor (Fig 19). The floor is then given light CGI roofing. These dwellings are now so called ‘half architecture’ and are utilized for kitchen and storage if not for sleeping in the night for fear of further possible shock. The remodeled two story dwelling and the temporary shed which could be at certain distance from the location of the dwelling complement the regular daily life of the inhabitants.

Fig 17a

Fig 17b

Fig 18

Fig 19

Fig 20

Clusters of temporary shed are built in open spaces within the city or in the open fields in the fringe (Fig 20). The sites are not the planned evacuation sites. A site in Bhaktapur used for emergency shelter that housed around 100 families suffered from a flood in August 27 and had to shift to other location. Most of the sheds are built with the support of NGOs and NPOs, and are of CGI sheets for both walls and roofing with meager floor space of about 12 sqm. The CGI unit was popularized by the donating agencies and by the state and the local government. However, the performance of such units both in summer and winter is evidently worse and is taking the toll on the health of the refugees particularly of the children, elderly, and adults who require health care. In the ongoing winter, reports of death due to the cold, particularly of elderly, are creeping in newspapers. The state is now giving Rs 10000 to warm the winter cold.

It is a pity to know that there was a general trend on the part of the refugees to wait for state or some philanthropic institution to come to their aid. Local skills and material that were in their reach was not called for. It was only late that there are peoples who rather than waiting any outside help relied back to their own local strength in building their shelter. The local building material and the skill certainly will prove beneficial to the inhabitants in the long run.

Fig 21a

Fig 21b

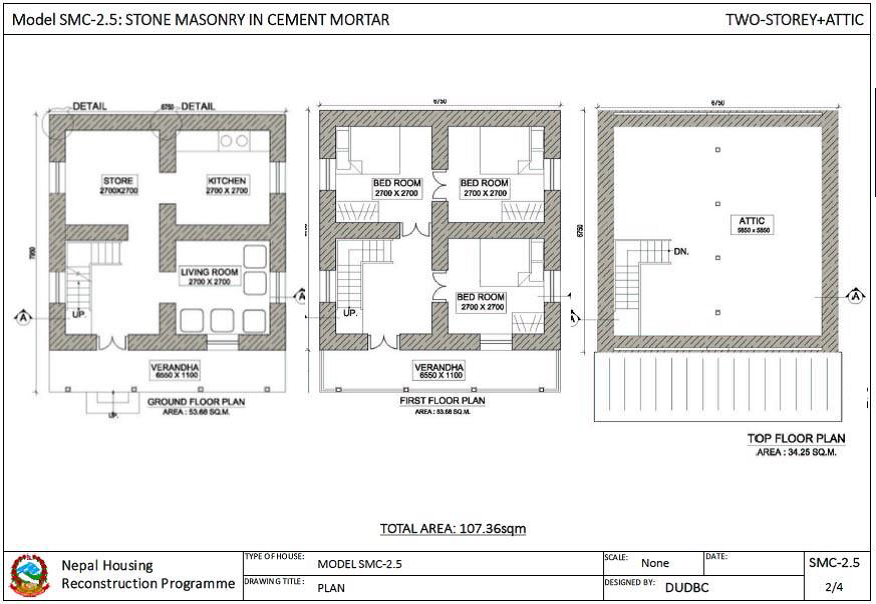

The state at the early stage of assessing the damage declared a package of financial assistance to those whose houses were completely damaged. The assistance is a flat amount of Rs 200,000 to both rural and urban households. In addition, Rs 25,00000 to the urban household and Rs 1500000 to the rural ones could be provided in the form of low interest against the bank mortgage. The assistance is planned to be provided in installments as the construction of the house proceeds in stages. Further the dwellings have to meet the new construction standard that is specifically tailored to withstand seismic movements. In terms of technical validity, the rules are of empirical nature. Department of Urban Development and Building Construction (DUDBC) under the Ministry of Urban Development, in November, produced a guideline to be followed and to be referred by the municipalities and rural village development committees. In addition, in October, the Department in collaboration with JICA published 17 model types as a guiding reference in the reconstruction of dwelling units in rural areas.[5] The models, in compliance with National Building Code 1994, are of masonry construction of single and double floors, and either in brick or stone with cement or mud mortar reinforced by RCC horizontal tying bands at plinth, sill, lintel and floor levels (Fig 21a, 21b).

Fig 22a

Fig 22b

But the models show lack of consideration of cultural patterns. They hardly reflect the floor plans or built forms of the houses that one finds in the rural settings of Nepal. However, certain instances of reconstruction effort from local initiatives that make a prior study of the locality and are sympathetic to the traditional dwelling form are coming up in the scene [6].

The PDNA puts forth a number of guidelines to follow in reconstruction process– community participation, coordinated effort of development partners, use of local resource and expertise, disaster risk reduction and resiliency, development of economic opportunities, environmental sustainability and equity. It also recommends the owner driven reconstruction process—the ODR. These theories of recovery have been formulated decades back, which carries much more weight in paper than in practice [7]. The financial support by the state to build the individual units is accepted by the people, but the low interest loan works in favor of the people with property to mortgage.

Immediately following the aftermath of the quake, the state put a moratorium in building constructions asking the people to wait until a new regulation was formulated. On November, the Ministry of Urban Development brought forth a set of guidelines that controls the design and construction of the building in both the rural and town areas.[8] To make these regulations work, there is a dire need of capacity building of the municipalities that now count to 217.

Further, the guidelines are to be adopted by respective municipalities while tailoring to their particular standards and needs. Historic towns of the Valley have special problems. After eight months, cities like Bhaktapur have not yet been able to come up with the new regulations. In this uncertainty, there are already instances of beginning of rebuilding by the households in their plots over the same footprint of the damaged building (Fig 22a, 22b).

A more progressive initiative in the reconstruction is shown by a community of Pilachen neighborhood at the eastern quarter of Patan. The locality has formed a community that includes around 85 households whose houses suffered various degree of damage. Their plan is to build together from the ground. But it is going to be in the same footprint of the earlier unit and will be built to meet the individual requirements of floor space. Community spaces such as streets and courtyards and shrines will be part of this community project. The project also explores new economic opportunities to attract tourists with facilities of home stay.

Concepts of urban regeneration are in the air and, occasionally, are the news highlights. However, the individual interests and conservative suspicions are a hard knot to crack, and hinder the way for a concerted community action. Municipality personnel can’t be excluded from this mindset.

Until now, the state has not taken initiatives to reconstruct the villages or the towns that have suffered a degree of damage that asks for the development in the scale of the village or a town block. It is at such places that the state will be in the position to realize the ‘Building Back Better’ concept embodied in the principle guidelines for reconstruction. This is also an opportunity to develop the areas that were inaccessible sectors of the quarter and where living environment were degrading due to excessive construction both in height and density. Entirely left to the principle of ODR, there is an evident danger that houses will be built in the same plots despite their inherent problems of access and difficult plot geometry making them similarly vulnerable to the future earthquakes. Steps towards this direction are urgently necessary to make the use of the financial resource effective that now takes around one third of the annual national development budget. The state should formulate relevant financial and legal framework for community action to support and guide the reconstruction initiatives. International Agencies and governments, such as the government of Japan, which has pledged the assistance of 30 billion yen for the post disaster recovery, should find a strategic framework of cooperation in this direction of housing and town building.[9] The state at least could build small pilot projects in association with the local communities and create an atmosphere where real life experience is possible that will guide the community further in the rehabilitation and reconstruction works.

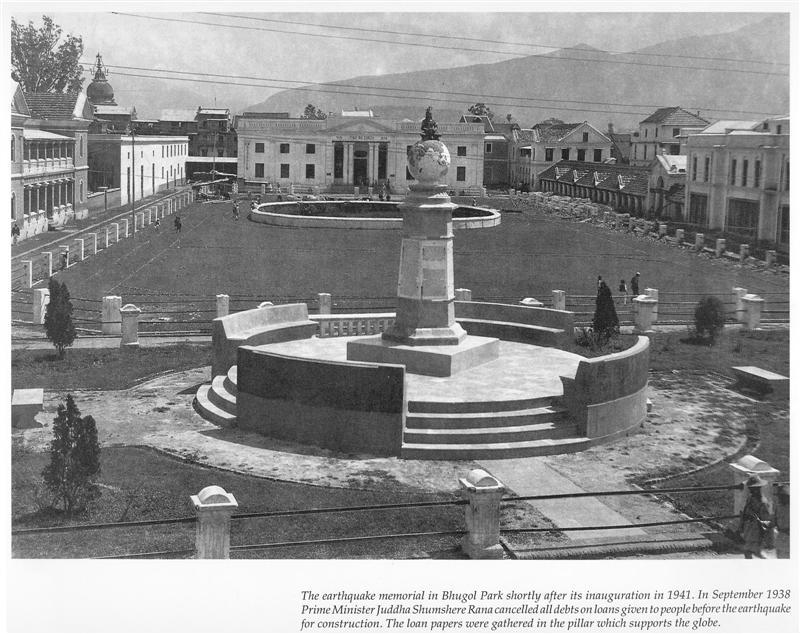

Fig 23

It is to be noted that following the 1934 earthquake a section at the southeastern part of the old city of Kathmandu was redeveloped introducing certain ideas of planning of the time (Fig 23). This experience almost is a forgotten past. Likewise, casual observation of the settlements of the Valley suggests an established tradition of community initiatives in building the towns.[10] It is only in modern times that the role of the state and of the community has devolved leaving all the responsibility to ODR. However, it is of importance to note that the post disaster reconstruction and rehabilitation work is an excellent opportunity to invoke the exemplary traditions the value of which will pay back any financial expenses made in this regard when meeting the present needs.

Gorkha bhukampa, 2072 (Gorkha Earthquake, 2015), Govt of Nepal, Jeth 12.

Milan Bagale, Barpak visit report (unpublished); Tandan, Pramod Kumar, Hakahaki, Dec 2072.

drrportal.gov.np

Nepal Earthquake 2015 Post Disaster Needs Assessment, Vol A: Key Findings; Vol B: Sector Reports. Govt of Nepal, National Planning Commission, Kathmandu, 2015.

Design Catalogue for Earthquake Resistant Houses, Vol 1, Govt of Nepal, Ministry of Urban Development and Building Construction, Nepal Housing Reconstruction Programme, 2015, Oct.

A reconstruction program in Gudel Village, Solukhumbu initiated by Gudel Kiduk Samaj and CODE, Kobe.

Gujarat Earthquake Reconstruction and Rehabilitation Policy (GSDMA), The Gujarat State Disaster Management Authority, 2001.

Vasti vikas, sahari yojana tatha bhaban nirman sambandhi mapadanda, 2072 (Standard on Housing, Town Planning and Building Construction, 2015), Ministry of Urban Development (MoUD), 2015 Oct.

The Himalayan Times > Business > Japan assistance for Nepal earthquake recovery, Dec 21, 2015. This is a follow up of the International Conference on Nepal’s Reconstruction held on June 25, 2015.

Stupa and Swastika—Historic Urban Planning Principles, Pant Mohan and Funo Shuji, 2007, Kyoto University Press.

最近のコメント